21.02.2024–15.03.2024

Exhibition Catalogue

Ilam Campus Gallery, School of Fine Arts, University of Canterbury

eat your mind

No “exhibition, the end”

By Orissa Keane

I told Isabella:1 need to see a floor plan, a room sheet if there is one, with a list of materials and artworks in each room. She sent me the list and a floor plan she’d made up quickly. This shows the fourteen rooms upstairs and down. I mustn’t be very observant because despite having looked at the documentation, I didn’t realise there was an upstairs, and just so many rooms, and actually what strikes me now is the sheer amount of work produced and installed within the building.

The Olivia Spencer Bower (OSB) award, aside from a show at Ilam Campus Gallery, demands only that the recipient spend their year prioritising their practice. For some, an artist residency offers time to work on an upcoming exhibition or project, but for many it can be purely for professional development, research, and play. Since my time as a student I remember these exhibitions punctuating the beginning of each year like an ampersand, and another artist represents something of their experience to an audience. This outcome has varied, from the deliberate A gathering distrust (2018) of Daegan Wells’, to Annie Mackenzie’s Sundries (2021) when the gallery held the artist's weaving loom alongside boxes of fibre and yarn (Annie was late to learn of the expectation of a show). So the research conducted during a year of the OSB becomes an exhibition, and just as research takes many forms and draws many varying outcomes, so too does the exhibition.

As is frequently the case with catalogue essays, there was not quite an exhibition yet to write about when I began; this conundrum is exaggerated because Isabella is responding in situ to the gallery. I chose to lean heavily on two things: one was Isabella’s studio exhibition two years I one building held over the summer at 214 Broadway, Tataenui (Marton); the other, a PDF that Emma Fitts had given to our sculpture class circa 2017: Artistic Research Methodology: Narrative, Power and the Public, by Mika Hannula, Tere Vaden and Juba Suoranta (2014). I zeroed in on a section titled ‘Part I – Fail Again, Fail Better’ from which I will borrow a few passages. The authors of Artistic Research refer to Paul Feyerabend's proposition, ‘anything goes’. “Anything goes” is the ultimate recognition that things must stay open and potential?01 In my understanding, this is a position of humility and an acceptance of a lack of knowledge, inviting research with no preconceptions as to outcome.

The authors argue though that without understanding the ‘historicality and context-boundedness’ of ‘anything goes’, there’s a danger of complacency and that a practice would descend into an insipid lateral sprawl.

In its most naked form, this attitude is sported like this: because I am an artist, and because I need to experiment, and because all materials and possibilities are accessible and open for me, I can do anything with everything and that anything I do, because I am an artist, is, in itself, interesting and significant. Amen.02

They say this is not a caricature, but nor is it ‘full-blown reality’.

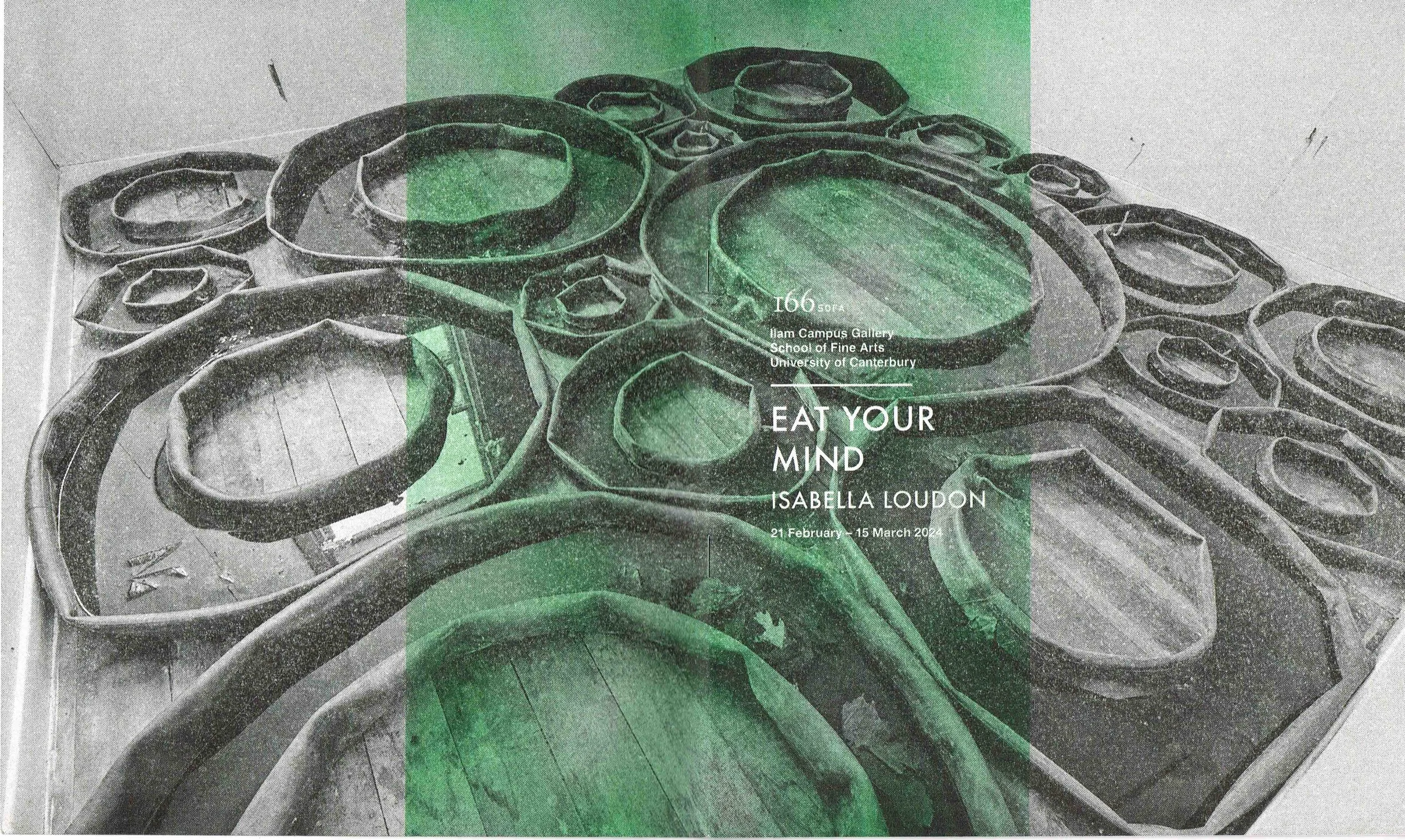

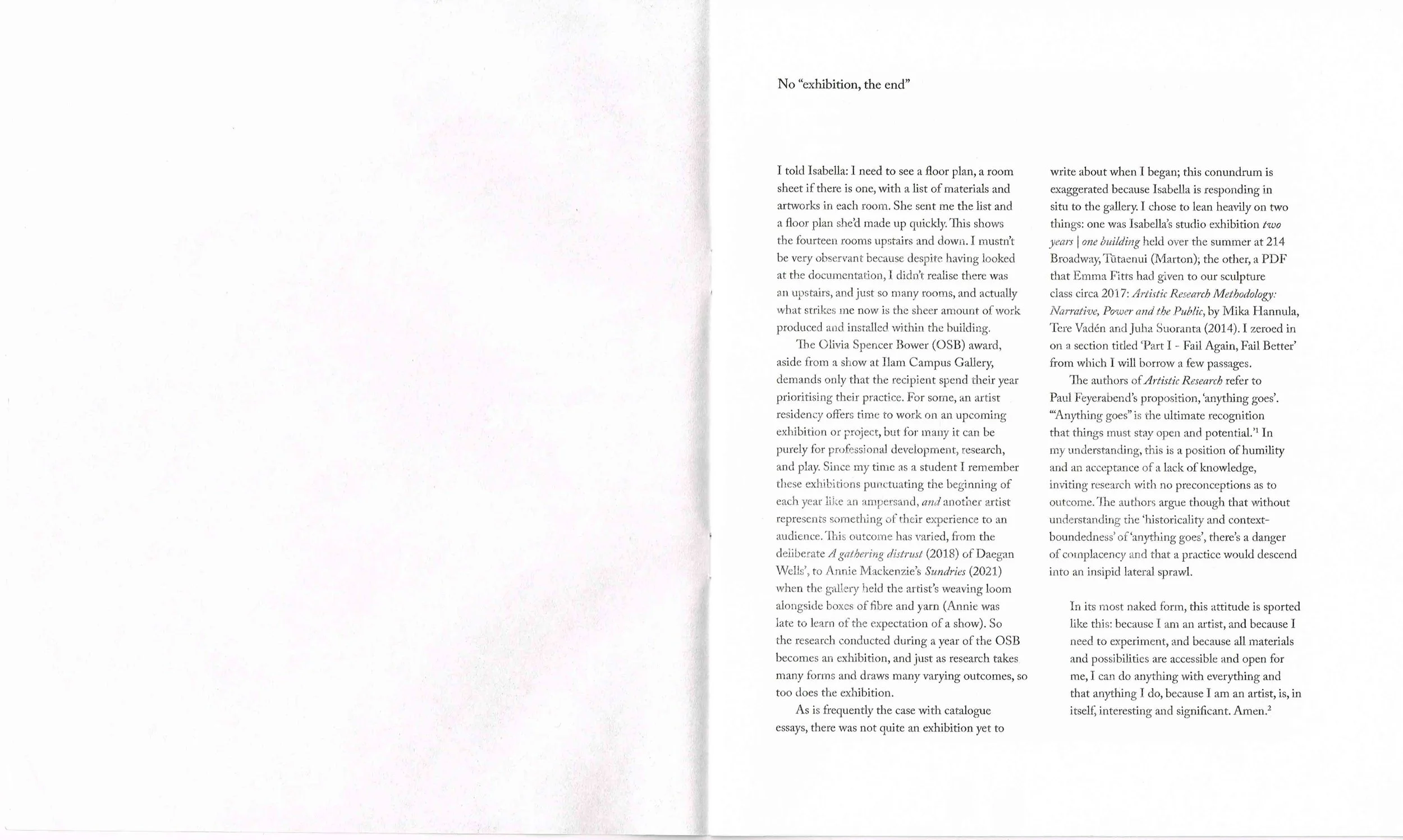

Isabella and I met at the opening event for The air, like a stone at The Physics Room in July last year. There was a dinner held in the gallery and we were seated near each other. After a while we introduced ourselves and started talking about concrete, how interesting and challenging it is to work with (interesting for all kinds of fun reasons, and challenging for environmental and health reasons). I’ve known her name and her work since my time at art school when I was working with plaster and concrete and testing ways of casting into soft materials. Isabella has been working with concrete for the last ten years building a lexicon of other media along the way, often plaster, twine, wire, various concrete pigments and more recently, rubber inner tubes. In two years I one building there are also a number of oilstick drawings, the oilsticks made by Isabella herself; they appear to be studies towards the sculptures. Thickly pigmented curving forms and hectic skinny scribbles evocative of her rubber tube works and concrete/twine pieces, respectively. Some of what’s in two years I one building is being remade or reinterpreted for Ilam Campus Gallery. But mostly, what’s left of the more site-specific installations will be demolished along with the building.

There’s a sly but strong sense of love and attachment within the gesture of making for a space which is scheduled to be destroyed. Attachment might seem a strange word for something the artist is prepared to let go of, but to use the word detachment would imply a kind of apathy which isn’t there. Beyond attachment, there's acceptance and a sense of mutuality between Isabella and the building which has hosted her studio for two years since moving back to Tutaenui.

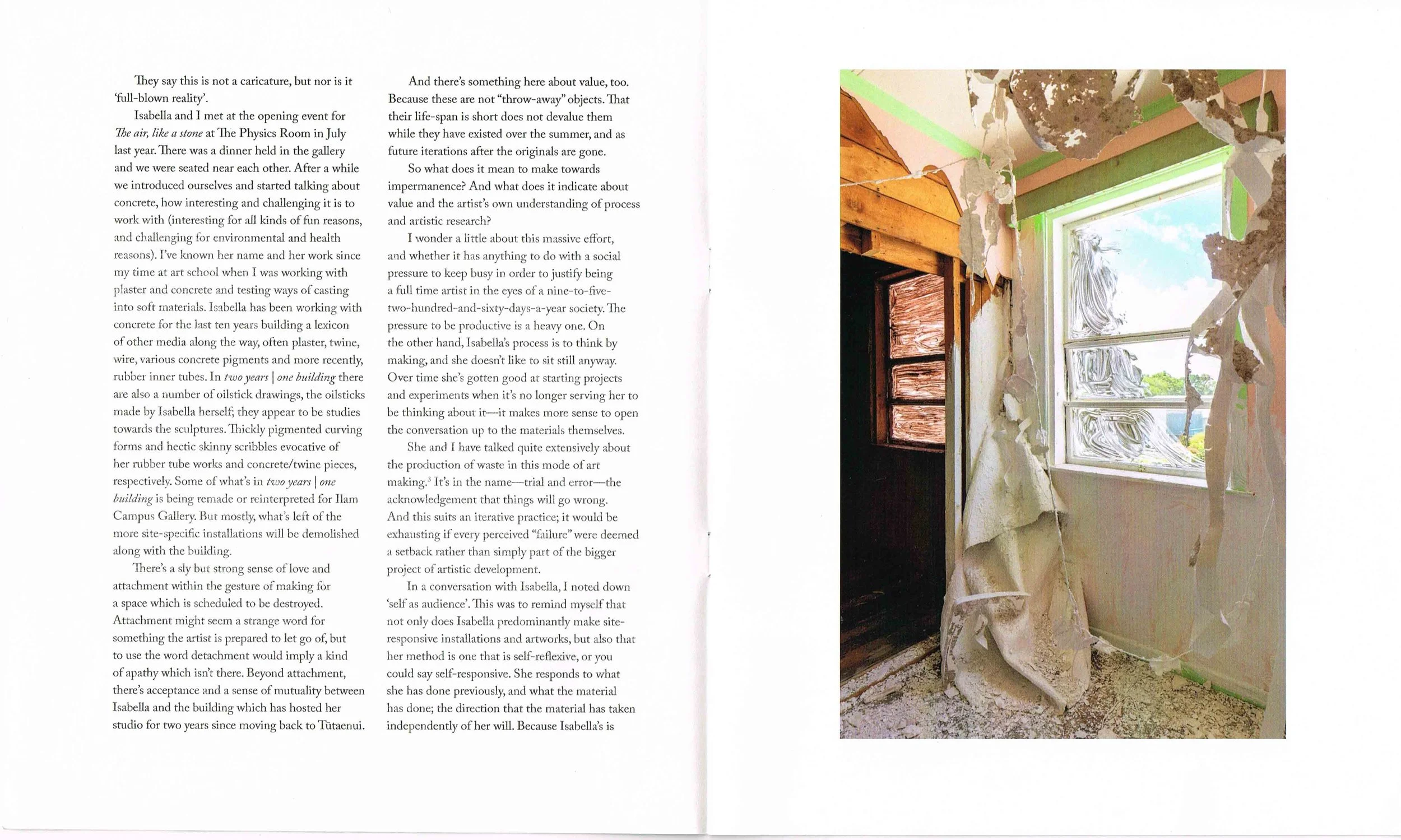

And there’s something here about value, too. Because these are not “throw-away” objects. That their life-span is short does not devalue them while they have existed over the summer, and as future iterations after the originals are gone. So what does it mean to make towards impermanence? And what does it indicate about value and the artist's own understanding of process and artistic research? I wonder a little about this massive effort, and whether it has anything to do with a social pressure to keep busy in order to justify being a full time artist in the eyes of a nine-to-five-two-hundred-and-sixty-days-a-year society. The pressure to be productive is a heavy one. On the other hand, Isabella’s process is to think by making, and she doesn't like to sit still anyway. Over time she's gotten good at starting projects and experiments when it's no longer serving her to be thinking about it—it makes more sense to open the conversation up to the materials themselves. She and I have talked quite extensively about the production of waste in this mode of art making.' It's in the name—trial and error—the acknowledgement that things will go wrong. And this suits an iterative practice; it would be exhausting if every perceived "failure" were deemed a setback rather than simply part of the bigger project of artistic development. In a conversation with Isabella, I noted down ‘self as audience’. This was to remind myself that not only does Isabella predominantly make site-responsive installations and artworks, but also that her method is one that is self-reflexive, or you could say self-responsive. She responds to what she has done previously, and what the material has done; the direction that the material has taken independently of her will. Because Isabella’s is often an intuitive making process, she relies on muscle and material memory.

It makes sense, in this way, that she’s not so precious about preserving all the works in two years | one building. It can be understood that here, impermanence places emphasis on the action of art-making, beyond exhibition-making.

There’s a part within ‘Fail Again, Fail Better’ which urges that artistic research be grounded in context, and ‘anything goes’, and careful editing. This makes for a messy sentence and a crude summary, but because any and all of these things can happen at once or in any order/over and over, I wanted them to be seen close together and side by side.

Isabella’s context is a long standing relationship with material and method, a knowledge of self and a grounding in site. For an exhibition, what’s important to Isabella is how people encounter the work: the presence of a sculpture in relation to a person entering the space; how a large or small group will interact with each other around/ between/through objects suspended or on the ground. It’s never something that can be predicted but something that is considered – to provoke a response. Whatever that may mean or manifest as, whether a feeling or a conversation prompted by a new association with common building materials or discarded objects like the rubber inner tubes. The rewarding feeling a viewer gets when the sculpture gives away something of the artist's process, as the liquid-to-solid process of concrete might do for some audiences. Or puzzlement at the weightlessness of timber on wire legs, or the unnamable bodily forms that the rubber tubes elicit.

“The exhibition” is not synonymous with “the end”. Isabella’s is a cyclical practice, folding, twisting and remaking itself constantly.

Endnotes

1. Mika Hannula, Tere Vadén, Juha Suoranta, “Fail Again – Fail Better”, Artistic Research Methodology: Narrative, Power and the Public, (New York: Peter Lang Publishing Group, 2014), 5. This is easily found and downloadable, it is ‘essential reading for university courses in art, art education, media and social sciences.’

2. Mika Hannula et al., Artistic Research Methodology, 2014, 7.

3. Get yourself a physical or digital copy of Correspondence 3.1: Conversations about the weather can no longer be regarded as small talk, 2023, edited by me, published by The Physics Room. In it you'll find a conversation between Isabella Loudon, Melissa Macleod and I titled ‘Material costs’. https://physicsroom.org.nz/publications/correspondence-31

Isabella Loudon is an artist currently based in the Rangitikei (NZ) working across the mediums of sculpture, installation and drawing. She uses easily sourced industrial materials to experiment with processes that are intuitive, chaotic and messy.

Throwing, hanging, soaking, draping, layering and inverting give her the opportunity to relinquish control and ‘discover’ the work, rather than plan and then execute it. Loudon received a Bachelor of Fine arts with first class honours from Massey University, Pöneke Wellington in 2016. She was the 2023 recipient of the Olivia Spencer Bower Award, Otautahi Christchurch.

Recent exhibitions include two years | one building, presented by Sarjeant Gallery Te Whare o Rehua (off-site project), Tutaenui Marton, 2023; lyre lyre, Robert Heald Gallery, Pōneke Wellington, 2023; self seeker, RM Gallery and Project Space, Tamaki Makaurau Auckland, 2022; morph, Trish Clark Gallery, Tamaki Makaurau Auckland, 2021; wastelands, Paptüanga, Tamaki Makaurau Auckland, 2020; Unravelled, City Gallery, Poneke Wellington, 2019 and Labyrinth, The Dowse Art Museum, Wellington, 2019.

Orissa Keane graduated from University of Canterbury with a BFA in 2019 and works as an exhibition technician at Te Puna o Waiwhetu Christchurch Art Gallery and as the Writing and Publications Coordinator at The Physics Room.

Acknowledgments

Olivia Spencer Bower Foundation, Simon Loudon & Felicity Wallace, Orissa Keane, Hugh Chesterman, Louise Palmer, Matt Burke, Sarjeant Gallery Whanganui & their team, Greg Donson, Andrew Clifford, Michael Mckegg, University of Canterbury, Michael Cranston, Trevor Hall, Aaron Beehre, Miah Borlase & the Ilam School of Fine Arts student volunteers.