Correspondence 3.1, The Physics Room, November 2023

Material costs: A conversation between Orissa Keane, Isabella Loudon, Melissa Macleod

Orissa Keane: I’ve been thinking about guilt and its function in relation to material use and processes. I know that for me there’s a constant weighing up of the varied costs of production, and a blind faith that what I do matters in some way and that its environmental impact is small and justifiable. I’ve noticed that guilt is a feeling that attaches to my lack of knowledge or belief in a clear solution. As artists who work primarily with objects and installation, I know you’re both very aware of your works’ environmental impacts, through your choice of materials and the production of waste.

Melissa Macleod: Yeah, I think sculpture gets disproportionately hammered with critique because materials are at the fore—they’re really visible. So both this self-criticism and to some extent external criticism falls on us unduly, really.

Isabella Loudon: I’ve been working with concrete for almost ten years now and I think a lot has changed in that time, specifically, our awareness of climate change and resources. How I feel now is very different to how I felt ten years ago. When I use concrete, I’m very aware of my health, but also that it creates waste. There will be leftovers, you can’t use every little bit and not everything works out.

OK: That’s an interesting point: what happens to the freedom to experiment when you’re worried about what happens when things go wrong? It’s not even waste, in terms of a wasted experiment—it’s a crucial part of making and trying things out. But the word ‘waste’ is so loaded, it strips it of the value it has within the rest of the process.

IL: Right, and in my work, gravity and chance play a big part, so I can’t necessarily just make it once. Sometimes the first time will be to test the idea, and then I make another version, and it’s the last one that works. But the five before don’t.

MM: And they go in the bin.

IL: Yeah and even when I try to reuse and repurpose things, I can’t save everything. I don’t think I could make the kind of work I’m making without working in that way. I wouldn’t make anything at all.

MM: It’s interesting, that process of making mistakes and what you do with that. And whether it can somehow be reincorporated, or if it’s just chucked out. Guilt is an interesting word, and I keep seeing the word responsible too. I’ve started to hate those two words the more I read, actually, around art’s place within the climate crisis.

IL: I’m finding it a real battle to use concrete at all now. I’ve been using plaster, which is not any better environmentally, really, but it’s not as bad for your health. When I had my basement studio in Wellington, I would be in there for hours and there was no ventilation—I was just wearing a mask. Even then, when you’re in there and you take it off, it’s all still in the air. I’ll feel it afterwards, if I’ve done concrete work. And then I wonder about those people who do it for a job, all the time.

When you use plaster and concrete, you get all these little shards and waste so I’ve been filling up a bucket of these bits and trying to put them into new works. Some have worked when it’s used as bulk fill but mostly I do it because I feel guilty for throwing it out.

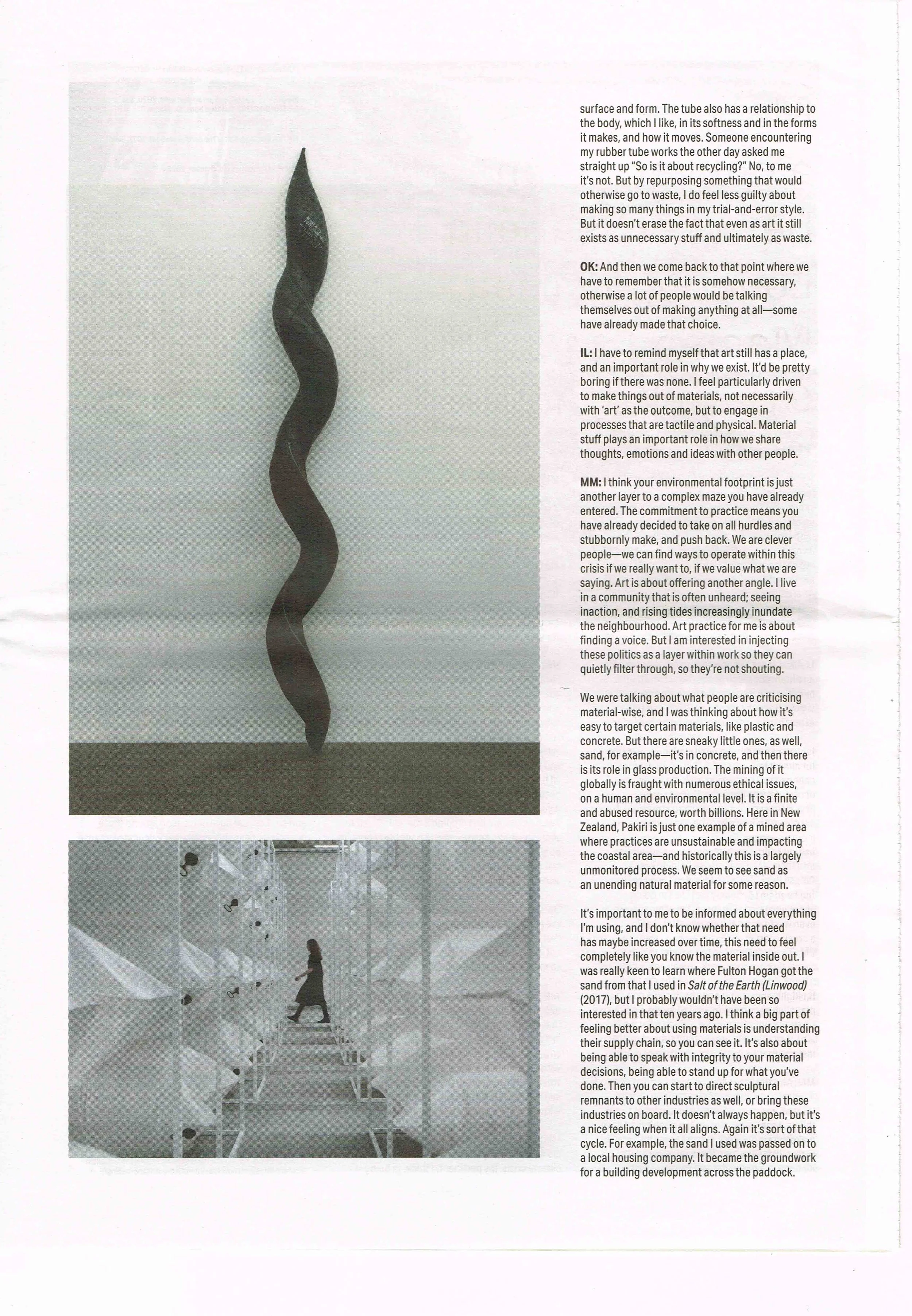

MM: The guilt, it’s attached to daily life and the need to be conscious and recycle everything. In the case of the plastic dunnage bags in my work on an east wind, 2020, how they were perceived shifted over the making time. Single use plastic shopping bags were banned in 2019 and plastic was such a news item. Part of me didn’t want to go ahead with the work.

OK: Was that because of how you thought the work would be received?

MM: Essentially. I was bracing myself for criticism, but interestingly it never came. In my mind, I’d found a product that I thought was fascinating, because dunnage bags are designed to pack shipping containers, and to be filled with air from different countries, which felt totally fitting conceptually. Their function made sense to my work as I was similarly filling them with sea air. And actually, that sort of contrast between plastic and air was interesting.

So ultimately it was a good material to work with. Equally, my material decisions extend to the freighting and afterlife of the work, the life cycle. For the air work, I’d planned for it to exist as multiple iterations. That work is large scale once it’s installed, but in its uninstalled state, can fit into a small compact area on the back of a ute. I think those considerations have increasingly come into play, an awareness of the mass of a work. The residue as well—where do you put it, if you’re even keeping it? And beyond that, what else could it be? Who could I give it to as a material? What industry might use it? Could it be sewn into something else? Or become linings for something? More and more this thinking becomes part of how I work when I’m starting from base up.

IL: There’s this image that NFTs and digital media are actually not taking up as much resources and space, but that’s not necessarily true. In some instances the printed version can be the better option for the environment rather than storing billions of emails, PDFs, images, videos etc on the internet, which require more and more servers and more warehouses which use more energy. But because we don’t see that, it’s hard to recognise it as a problem.

OK: Same as the rubbish at the dump, right? We can call to mind an image of a pile of rubbish, but it’s hard to comprehend or imagine the scale at which it actually exists in relation to us.

MM: I think as artists, we don’t want to own all this. I think that’s why the Frieze article by Tom Jeffreys, Challenging the Art World’s Material Waste (2021) was interesting. The article places the onus back on art institutions; environmental accountability needs to be embraced by the whole art mechanism, including gallery processes, and buyers. It can’t be all on artists. Just as one small example, sometimes the perceived pressure to use materials we don’t want to, for environmental reasons, is partially due to limited funding.

IL: I think it depends on how you want the work to be read as well. If we start to look at art always through an environmentally concerned lens, then all other ideas are dulled. I love using concrete, its grittiness, its transition from liquid to solid, and the way you can cover things and it envelops them. Now, though, whenever I use it I am always concerned that work is going to be criticised first and foremost for being materially harmful for the environment. I’m not sure if this is true, but it definitely weighs on me.

OK: I wonder how it’s possible to have it both ways and say “fuck it, I really like the material and I want to play and explore it”. But to also make it work within an ethical framework which considers the environment? Or if they will always be opposing priorities?

MM: I’ve noticed artists who are consciously choosing natural materials, where in some instances those materials can be so loaded that the initial concept is drowned out by the material choice. In itself, the fact that an artwork can biodegrade is really interesting, but in these cases, actually it wasn’t meant to be the dominant aspect of the work. But that’s where our focus is directed right now, on sustainability.

IL: I think I’m definitely getting quite confused at the moment, I try really hard to reuse, repurpose, buy secondhand clothes, buy things that will last. But in my practice, I’m not interested in those things becoming the focus of the work. I’ve been working a bit with used rubber inner tubes. What drew me to the material is that it evoked something—these found materials have a past and this is reflected in their surface and form. The tube also has a relationship to the body, which I like, in its softness and in the forms it makes, and how it moves. Someone encountering my rubber tube works the other day asked me straight up “So is it about recycling?” No, to me it’s not. But by repurposing something that would otherwise go to waste, I do feel less guilty about making so many things in my trial-and-error style. But it doesn’t erase the fact that even as art it still exists as unnecessary stuff and ultimately as waste.

OK: And then we come back to that point where we have to remember that it is somehow necessary, otherwise a lot of people would be talking themselves out of making anything at all—some have already made that choice.

IL: I have to remind myself that art still has a place, and an important role in why we exist. It’d be pretty boring if there was none. I feel particularly driven to make things out of materials, not necessarily with ‘art’ as the outcome, but to engage in processes that are tactile and physical. Material stuff plays an important role in how we share thoughts, emotions and ideas with other people.

MM: I think your environmental footprint is just another layer to a complex maze you have already entered. The commitment to practice means you have already decided to take on all hurdles and stubbornly make, and push back. We are clever people—we can find ways to operate within this crisis if we really want to, if we value what we are saying. Art is about offering another angle. I live in a community that is often unheard; seeing inaction, and rising tides increasingly inundate the neighbourhood. Art practice for me is about finding a voice. But I am interested in injecting these politics as a layer within work so they can quietly filter through, so they’re not shouting.

We were talking about what people are criticising material-wise, and I was thinking about how it’s easy to target certain materials, like plastic and concrete. But there are sneaky little ones, as well, sand, for example—it’s in concrete, and then there is its role in glass production. The mining of it globally is fraught with numerous ethical issues, on a human and environmental level. It is a finite and abused resource, worth billions. Here in New Zealand, Pakiri is just one example of a mined area where practices are unsustainable and impacting the coastal area—and historically this is a largely unmonitored process. We seem to see sand as an unending natural material for some reason.

It’s important to me to be informed about everything I’m using, and I don’t know whether that need has maybe increased over time, this need to feel completely like you know the material inside out. I was really keen to learn where Fulton Hogan got the sand from that I used in Salt of the Earth (Linwood) (2017), but I probably wouldn’t have been so interested in that ten years ago. I think a big part of feeling better about using materials is understanding their supply chain, so you can see it. It’s also about being able to speak with integrity to your material decisions, being able to stand up for what you’ve done. Then you can start to direct sculptural remnants to other industries as well, or bring these industries on board. It doesn’t always happen, but it’s a nice feeling when it all aligns. Again it’s sort of that cycle. For example, the sand I used was passed on to a local housing company. It became the groundwork for a building development across the paddock.

IL: I prefer not to know where things come from or to know too much about them. I feel it affects my initial impressions of a material and freedom to explore what it can do. By finding materials, rather than buying them, they come loaded with their own history, it’s just not one I can know. But there is something liberating in redirecting or repurposing a material that would otherwise go to waste. Also making art is expensive, the more that’s free the better! When I went to Whanganui I went to a bike shop and asked, have you got any bike tubes? They gave me a barrel.

But you know, those people were also holding onto them. More people are holding onto things I think, because they don’t want to throw them out. So I definitely feel like I’m doing something good with those. I’m using them in an artwork but what happens after that?

MM: It’s interesting too to consider that artists aren’t always making good work. Not all environmental artwork is successful, and what they’re talking about might be being done better by a community project or by a scientifically led group. Sometimes artists are not very good at editing what we think is worthy and appropriate subject matter. Sometimes art’s not the best vehicle or medium.

OK: There are times when it would be just as good or better to be just pointing at a thing, like to use your voice or platform to just point at these things that already exist, to the people who have already done the work. It can seem a bit parasitic when artists take from these initiatives if it’s not done in a particular and sensitive way.

MM: That’s when it hasn’t had a shift has it? Artists have taken something real and researched, and haven’t reimagined it. I think the shift in that process is where this topic can become interesting, when something quite banal is manipulated and can be seen from a different angle. We have to be really aware of not just taking, which can easily occur, and thinking that putting an idea in a gallery is all it needs. That is something I’m really aware of because I’m often dealing with scientific research. It’s really crucial that you’re sensitive around that. Because you are just dipping a toe, compared to someone who’s been studying a specialty area for 50 years. You’re taking some often really detailed, fascinating material, that is totally someone’s world and sort of using what you need from it.

OK: And it’s easy to think that it’s justified because the artist is representing that information to a public that might not otherwise be exposed to it but that’s not always enough. I’m guilty of being drawn to a specific and poetic idea from science and wondering what I can do with it. It’s a trope of art making, once you start recognising it. It’s when that next step hasn’t been taken or hasn’t been executed in full that we’re talking about being potentially harmful in its purposelessness. I know that science fiction, and speculative fiction is becoming quite a good vehicle for imagining the future in terms of climate adjustment, and artists are looking to fiction increasingly. It does take from science and present it for its own ends but it does so in a generative way.

MM: It’s a really integral relationship at the moment, for artists that want to be a voice for climate crisis. It’s pertinent, I think, in being able to learn from other research worlds and speak from a place of knowledge, because you can’t come up with everything, you know, why would you come up with everything yourself? There are other industries and researchers out there that are interested in that collaboration.

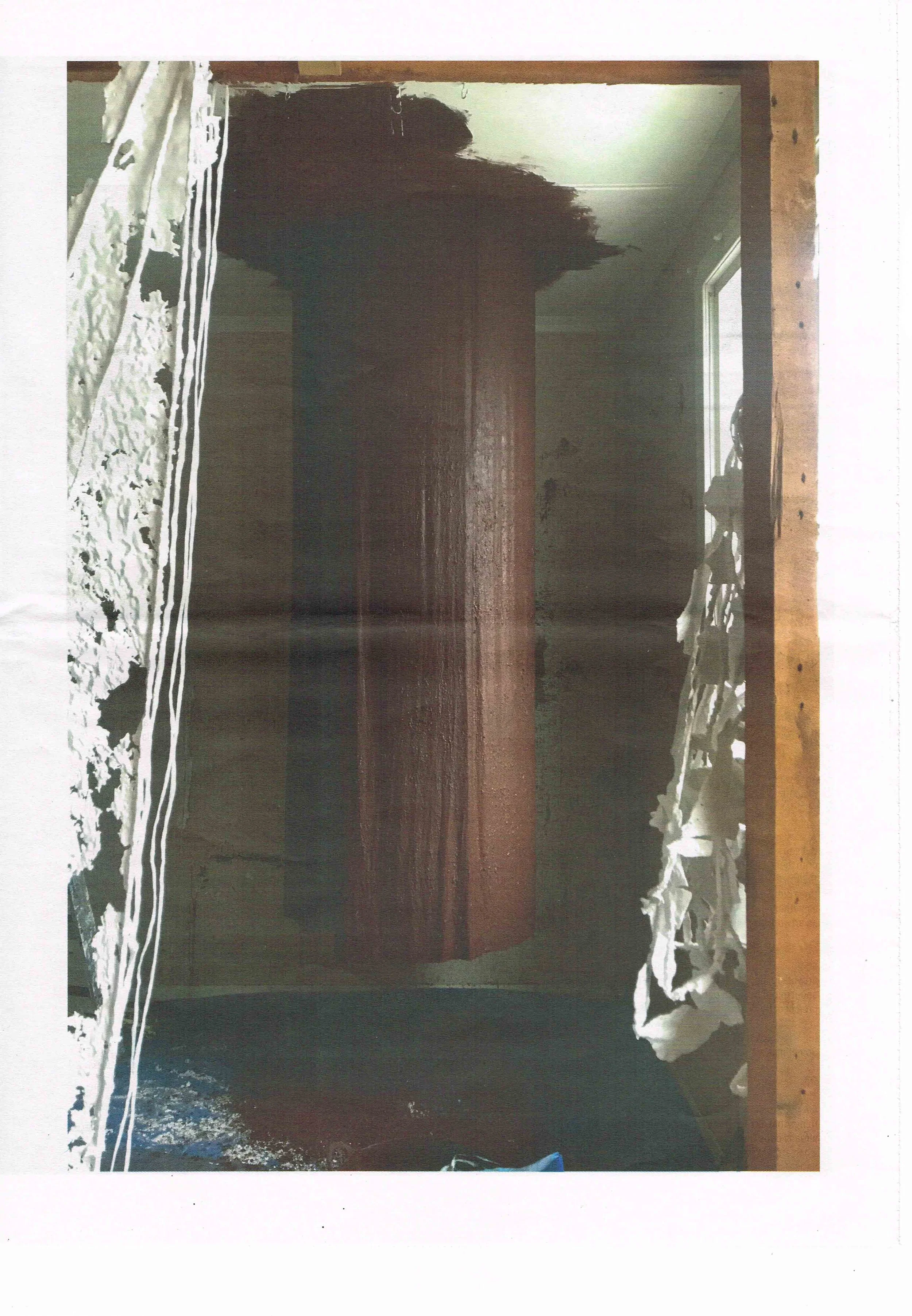

Currently I’m looking at taking sea samples from areas that have flooded houses. There’s lots of scientific information from the likes of the National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research (NIWA), and studies that have been done around these impacted communities. It’s really delicate because I’m also dealing with people’s lived experiences of having had their houses and lives devastated. I’m conscious of the need to stand back and remember where my practice sits within this very real and lived space. There’s a balance to find when you’re essentially ‘using’ experiences of environmental crises, and wanting to make an art show from it.

In researching this topic, we looked to these sources and more for reference.

We mention ‘the Frieze article’, which is called Challenging the Art World’s Material Waste (2021) by Tom Jeffreys. https://www.frieze.com/article/challenging-art-worlds-material-waste

The essay discusses Helen Mirra’s 2019 manifesto CATHARTES 19, setting out a series of principles and practices responding to concerns for climate collapse, plastic waste and the treatment of nonhuman living beings. https://www.hmirra.net/information/pdfs/CATHARTES19_circular.pdf

Here is some basic information about sand mining from Friends of Pakiri Beach, an organisation aiming to stop sand mining at Pakiri. The legal battle is ongoing against the McCallum Brothers. https://friendsofpakiribeach.org.nz/sand-mining/