08.12.2023-10.12.2023

214 Broadway Tūtaenui Marton

Presented with the support of Sarjeant Gallery Te Whare o Rehua Whanganui

Photos by Michael McKeagg

Art News, Autumn 2024

‘ISABELLA LOUDON two years, one building’

By Millie Riddell

“Plaster!” wrote Eva Hesse in her diary, 10 December 1964. “I have always loved the material. It is flexible, pliable, easy to handle in that it is light, fast-working. Its whiteness is right.”01 At the time, Hesse was working in an abandoned factory building in Kettwig-am-Ruhr, Germany. Lucy Lippard called it a “lonely but crucial apprenticeship”; surrounded by the debris of the former textile factory, Hesse began to experiment with found materials, leading to a shift from painting to sculpture, and a practice that emphasised process, ritual, repetition and, first and foremost, material.02

Hesse’s raptures over plaster and its dazzling whiteness could be referring to a room upstairs, just off the kitchen, at 214 Broadway, Marton, where reams of plaster, fibre tape and twine hang from the ceiling and along the walls, suspended above even more shards of plaster covering the carpet. This is the space Isabella Loudon has occupied for the past two years, a former Chinese takeaway and bookshop slated for demolition later this year. The result is two years, one building, a solo show meets open studio, with the entire building given over to Loudon's messy, material-driven practice.

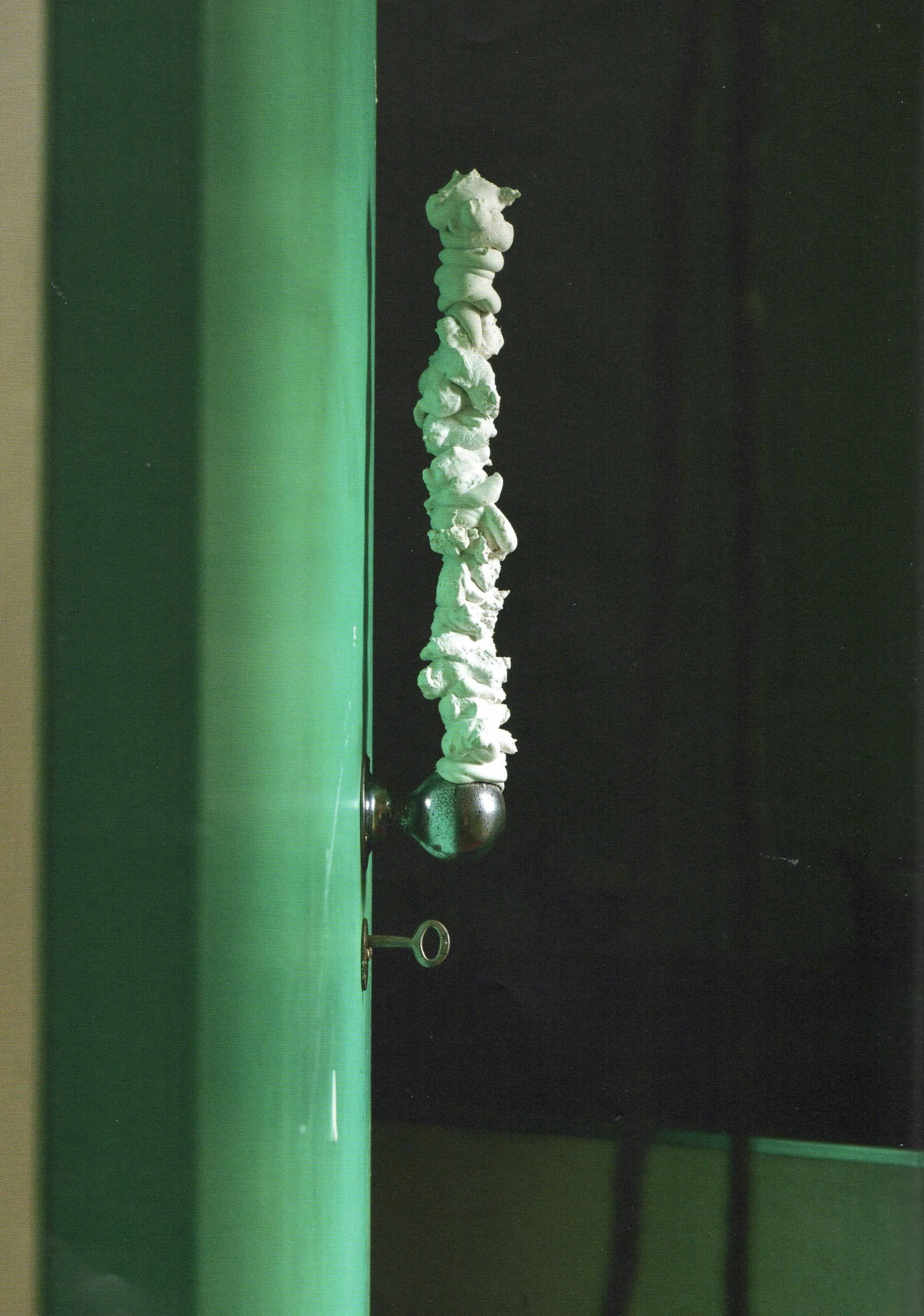

Loudon works with difficult materials: concrete, tyres, fencing wire, plaster, baling twine, rubber tubes, nails, lawn-mower belts, wood, steel, oxide. She will often combine, at most, two different materials—twine and concrete, twine and plaster, wood and wire—exploring the interactions and dependencies of putting the two together. The scale of two years, one building allows for repetition and experimentation, for the visibility of Loudon’s process of testing the limits of her materials. The experiments in the plaster room echo in more realised works elsewhere—a tarpaulin poking through its plaster casing on the floor a few rooms over, hanging sheets of plaster and twine in the window to the street, tarp peeled away this time. In the adjacent window, a butcher-esque display of sliced tyres hangs in coils, a reminder that gravity is as much a material as anything else here.

Form, with all its suggestion of finality and some measure of artistic control, feels less important than the other forces at play—chance, failure, space, time. Smears of plaster and concrete line the walls behind works, visualising the mess and excess energy left over from the process of making, blurring the boundaries between object and the space it occupies. In a small square room upstairs, three concrete columns hang from above, the walls and ceiling coated with the same red-and-black oxide-coloured concrete. This was the point where Loudon realised she could build directly into the space itself, that the barrier between site and work could dissolve. She stapled sheets to the ceiling and then, from a ladder, from a ladder, covered them in concrete to set these strange, hollow pillars—a death mask of negative space. They stop somewhere around knee height, an awkward end-point designed to restrict movement in the space and shift our gaze around the room, out the window, through the doorway to the adjoining rooms.

A house, Gaston Bachelard reminds us in The Poetics of Space, is never just a house.03 Whenever art is made in, or made to evoke, domestic spaces, we often turn to the uncanny. Objects out of place, materials not quite behaving how we expect—maybe a concrete pillar with the soft folds of fabric—hovering between comfort and trauma. Loudon does not manipulate memories of the former domestic space upstairs, but nor does she ignore them. The bathroom, with its blue acrylic bathtub and patterned wallpaper, houses, suitably, the most bodily objects in the show—concrete-encased twine shudders its way out of the bath; opposite sits an old noticeboard so heavily layered in plaster, oxide, elastic thread, nails, pins, string and more plaster that it hints at a fossilised creature, either just buried or just emerging. The delicate balance of the materials she fuses together, of soft and hard, pliable and fixed, the industrial materials repurposed in a new setting, evokes a Bourgeois-esque sensation of a building bleeding its own unconscious.

“Common sense lives on the ground floor,” Bachelard writes. To go upstairs “is to withdraw, step by step, while to go down to the cellar is to dream, it is losing oneself in the distant corridors of an obscure etymology, looking for treasures that cannot be found in words.”04 There is no cellar at 214 Broadway, but there is a long narrow corridor under the stairs, leading to a locked door (Loudon never found the key). Endless lengths of baling twine fill the space now, hung from nails in the ceiling and coated, through a process of washing and massaging, in dark-brown oxide-coloured concrete. The concrete worked into the individual threads thickens the twine as if from the inside, solidifying its soft form into something durable, fixed. Something as integral to the space as the bones of the building itself.

01 Lucy Lippard, Eva Hesse (New York: New York University Press,1976), 28.

02 Ibid, 47.

03 Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space (Boston: Beacon Press, 1958).

04 lbid, 147.