Art New Zealand, Summer 2020

Stretch and break

By Lucy Jackson

Isabella Loudon makes artworks that test the boundaries of form and material – messy, fraught, evolving and bold. Lucy Jackson visits the artist’s studio to examine her experiments in progress.

There is something a bit gnarly and gory about Isabella Loudon’s concrete-infused forms. Made with such industrial materials as concrete, metal, rubber and latex, Loudon’s artwork could easily be imagined in an apocalyptic wasteland, where the ancient and futuristic, manufactured and organic collide. The result is a feeling of unease. The viewer may not be sure of where they sit in this wasteland – did they create this world, or cause it to crash?

Uneasily, I have to be careful where I step as I walk through Loudon’s Wellington studio. Artworks line every inch of the space: spiky metal sculptures sit on the floor, while great concrete sculptures lean against walls and hang from a central beam. New and old sculptures sit on plinths, with concreted twine hanging from them; and latex works in progress snake across the floor. I recognise some artworks, such as Screen time (2019), from earlier exhibitions, and I’m not surprised – it must be difficult to store, and sell, large concrete sculptures. The studio is a physical representation of Loudon’s practice: steeped in industrial materials and with a working space that is constantly being shaped and reshaped.

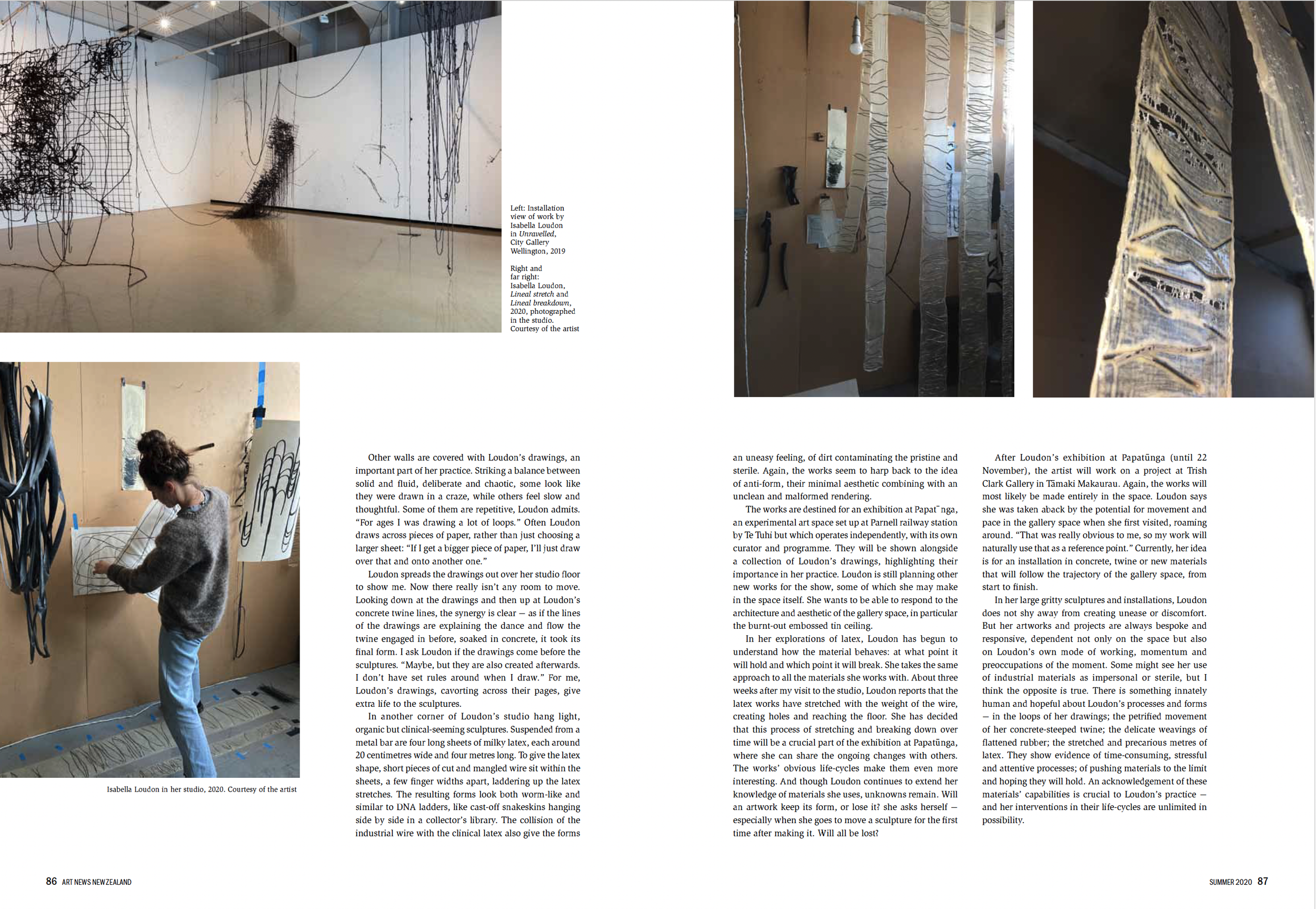

In 2016, Loudon graduated from Massey University of Wellington with a Bachelor of Fine Arts with Honours. Since then, the artist has had solo and group exhibitions in Wellington and Auckland. Loudon’s most recent exhibition was at City Gallery Wellington, as part of the group exhibition Unravelled, an exhibition about antiform – a deliberate move away from minimalism and structure and towards disorganisation and the breaking down of regulated forms.

Loudon’s contribution to Unravelled both commandeered and commanded the gallery, playing confidently with the mechanics of the space. Hanging from the roof were two large metal grid forms. One was suspended on its side like a floating painting, and the other hung heavily, as if it were being pulled up by its shoulders from the ground, gravity tugging insistently the other way. Concrete-encrusted twine interwove and hijacked the grid patterns, pushing the notion of disorganisation and mess, while other lengths of twine were roped around the surrounding area, hung from the ceiling and draped over the floor. An accidental splash made by a concrete-soaked paintbrush colliding with a gallery-white wall during installation became a feature of the exhibition – Loudon and the gallery staff continued to fling it onto the walls, making additional splashes.

Loudon says now that Unravelled represented a finite moment in her practice; this exact installation will not be repeated. She prefers to work in an ever-changing, adaptive way – right up until an exhibition is hung. With Unravelled, Loudon changed her plan for the exhibition one week before the install, when she started to move her grid features in her studio for transport to the gallery. The artist realised that she preferred the way they performed in a new alignment, rather than their original orientation. When she told City Gallery about her plan to adapt her exhibition, the curators were a little confounded.

Although Loudon’s practice is especially indebted to concrete, she is comfortable exploring other mediums and methods. Her studio highlights this. I’m especially drawn to a wall covered with what I see as ‘bouquets’ of rubber tubing, bunched together in odd arrangements. “I’m still trying to work those out,” Loudon says. They’re not bouquets, strictly, but rather experiments in an ongoing exploration of shape and form. In Format (2019), for example, Loudon transformed her rubber material into a minimal and formal sculpture. The rubber inner tubes from bike tyres were cut open and flattened, and then meticulously punctured by metal rods, resulting in a woven appearance for the top two-thirds of the sculpture. In the bottom third, the rods stop and the inner tubes hang and twirl freely. The control is lost.

Other walls are covered with Loudon’s drawings, an important part of her practice. Striking a balance between solid and fluid, deliberate and chaotic, some look like they were drawn in a craze, while others feel slow and thoughtful. Some of them are repetitive, Loudon admits. “For ages I was drawing a lot of loops.” Often Loudon draws across pieces of paper, rather than just choosing a larger sheet: “If I get a bigger piece of paper, I’ll just draw over that and onto another one.”

Loudon spreads the drawings out over her studio floor to show me. Now there really isn’t any room to move. Looking down at the drawings and then up at Loudon’s concrete twine lines, the synergy is clear – as if the lines of the drawings are explaining the dance and flow the twine engaged in before, soaked in concrete, it took its final form. I ask Loudon if the drawings come before the sculptures. “Maybe, but they are also created afterwards. I don’t have set rules around when I draw.” For me, Loudon’s drawings, cavorting across their pages, give extra life to the sculptures.

In another corner of Loudon’s studio hang light, organic but clinical-seeming sculptures. Suspended from a metal bar are four long sheets of milky latex, each around 20 centimetres wide and four metres long. To give the latex shape, short pieces of cut and mangled wire sit within the sheets, a few finger widths apart, laddering up the latex stretches. The resulting forms look both worm-like and similar to DNA ladders, like cast-off snakeskins hanging side by side in a collector’s library. The collision of the industrial wire with the clinical latex also give the forms an uneasy feeling, of dirt contaminating the pristine and sterile. Again, the works seem to harp back to the idea of anti-form, their minimal aesthetic combining with an unclean and malformed rendering.

The works are destined for an exhibition at Papatūnga, an experimental art space set up at Parnell railway station by Te Tuhi but which operates independently, with its own curator and programme. They will be shown alongside a collection of Loudon’s drawings, highlighting their importance in her practice. Loudon is still planning other new works for the show, some of which she may make in the space itself. She wants to be able to respond to the architecture and aesthetic of the gallery space, in particular the burnt-out embossed tin ceiling.

In her explorations of latex, Loudon has begun to understand how the material behaves: at what point it will hold and which point it will break. She takes the same approach to all the materials she works with. About three weeks after my visit to the studio, Loudon reports that the latex works have stretched with the weight of the wire, creating holes and reaching the floor. She has decided that this process of stretching and breaking down over time will be a crucial part of the exhibition at Papatūnga, where she can share the ongoing changes with others. The works’ obvious life-cycles make them even more interesting. And though Loudon continues to extend her knowledge of materials she uses, unknowns remain. Will an artwork keep its form, or lose it? she asks herself – especially when she goes to move a sculpture for the first time after making it. Will all be lost?

After Loudon’s exhibition at Papatūnga (until 22 November), the artist will work on a project at Trish Clark Gallery in Tāmaki Makaurau. Again, the works will most likely be made entirely in the space. Loudon says she was taken aback by the potential for movement and pace in the gallery space when she first visited, roaming around. “That was really obvious to me, so my work will naturally use that as a reference point.” Currently, her idea is for an installation in concrete, twine or new materials that will follow the trajectory of the gallery space, from start to finish.

In her large gritty sculptures and installations, Loudon does not shy away from creating unease or discomfort. But her artworks and projects are always bespoke and responsive, dependent not only on the space but also on Loudon’s own mode of working, momentum and preoccupations of the moment. Some might see her use of industrial materials as impersonal or sterile, but I think the opposite is true. There is something innately human and hopeful about Loudon’s processes and forms – in the loops of her drawings; the petrified movement of her concrete-steeped twine; the delicate weavings of flattened rubber; the stretched and precarious metres of latex. They show evidence of time-consuming, stressful and attentive processes; of pushing materials to the limit and hoping they will hold. An acknowledgement of these materials’ capabilities is crucial to Loudon’s practice – and her interventions in their life-cycles are unlimited in possibility.